What if I told you that Wizards of the Coast is just one of many publishers of Dungeons & Dragons? Sounds strange? WotC are the commercial owners of the D&D brand, and anyone stupid enough to use it without consent would get sued to oblivion. That, however, does not mean other publishers aren’t releasing great games that are just as much D&D as the game made by the trademark owner.

Why consider avoiding Wizards of the Coast?

But let’s just take a step back and discuss why you consider alternatives to Wizards D&D.

Well, first of all – maybe you shouldn’t. If you really enjoy the fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons, and don’t have a problem with the company Wizards of the Coast, then you’re all good. You should do what makes you happy. If you’re happy with D&D 5e then by all means – play it!

However …

- Perhaps you just don’t like fifth edition D&D.

- Maybe you have a problem with how WotC conducts their business or,

- you’re worried that they will step into the NFT (safe link, Wikipedia) space like their parent company Hasbro?

There are many valid reasons why to step away from whoever owns the commercial rights to put a Dungeons & Dragons logo on their book cover. Also; you don’t even need a reason other than being curious and wanting to try something new.

But is it really Dungeons & Dragons if it doesn’t say so on the cover?

Short answer: yes!

Longer answer: yes! You see, there’s something called the Open Gaming License (OGL), which makes it legal to create clones of D&D. You can basically copy the rules and publish them under a different name than Dungeons & Dragons. The OGL is what Paizo used in 2009 to create the Pathfinder RPG, which outcompeted fourth edition D&D.

Here, let me quote whoever described the OGL on Wikipedia:

Dungeons & Dragons retro-clones are fantasy role-playing games that emulate earlier editions of Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) no longer supported by Wizards of the Coast.

They are made possible by the release of later editions’ rules in a System Reference Document under the terms of the Open Game License, which allow the use of much of the proprietary terminology of D&D that might otherwise collectively constitute copyright infringement.

These rules lack the name D&D or any of the associated trademarks.

Wikipedia

Many of such clones exist today, and they’re gaining popularity as roleplayers are switching from fifth edition to other alternatives. Some of these games are bunched together under the Old-School Reinassance movement, but wether you like that specific playstyle or not these games can be played in any way you prefer.

Games created and published under the OGL are sometimes exact clones of earlier editions of D&D (like Old-School Essentials), but more often they are tweaked, keeping the D&D core but making adjustments and additions to the rules and mechanics. In any case, most of these games are usually compatible – so you can use adventures from one game and play it with the rules of another!

So you see what I mean when I say it doesn’t need to say Dungeons & Dragons on the cover of the book to be D&D.

Ok, so what are my options?

Plenty, believe me. There are tons of D&D clones out there. Some of the most popular ones are Labyrinth Lord, Lamentations of the Flame Princess, Swords & Wizardry, White Box and OSRIC.

I’d like to put the spotlight on two major alternatives to fifth editions Dungeons & Dragons – Old-School Essentials and Dungeon Crawl Classics.

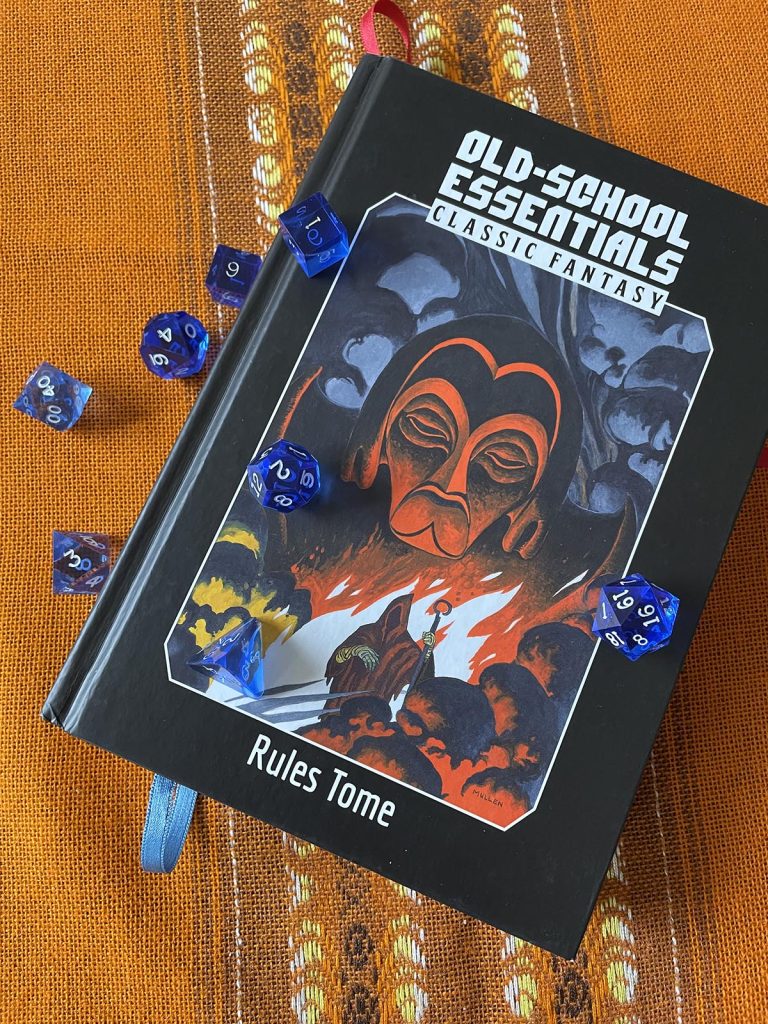

Old-School Essentials – for the D&D purist

Old-School Essentials (OSE) by Necrotic Gnome is an exact replica of the Basic/Expert mechanics of the game from 1981. If you choose the basic OSE you get the rules from D&D, just presented in a modern and more intuitive layout. It’s easy to read, wonderfully illustrated and just a really solid product that oozes quality.

OSE also has “advanced” supplements that add options that are not cloned from D&D but harmonizes really well with it. I recommend starting with the basic “classic fantasy rules tome” though, it’s just awesome.

The rules of D&D Basic Expert, ahem I mean Old-School Essentials are available for free online in the system reference document database.

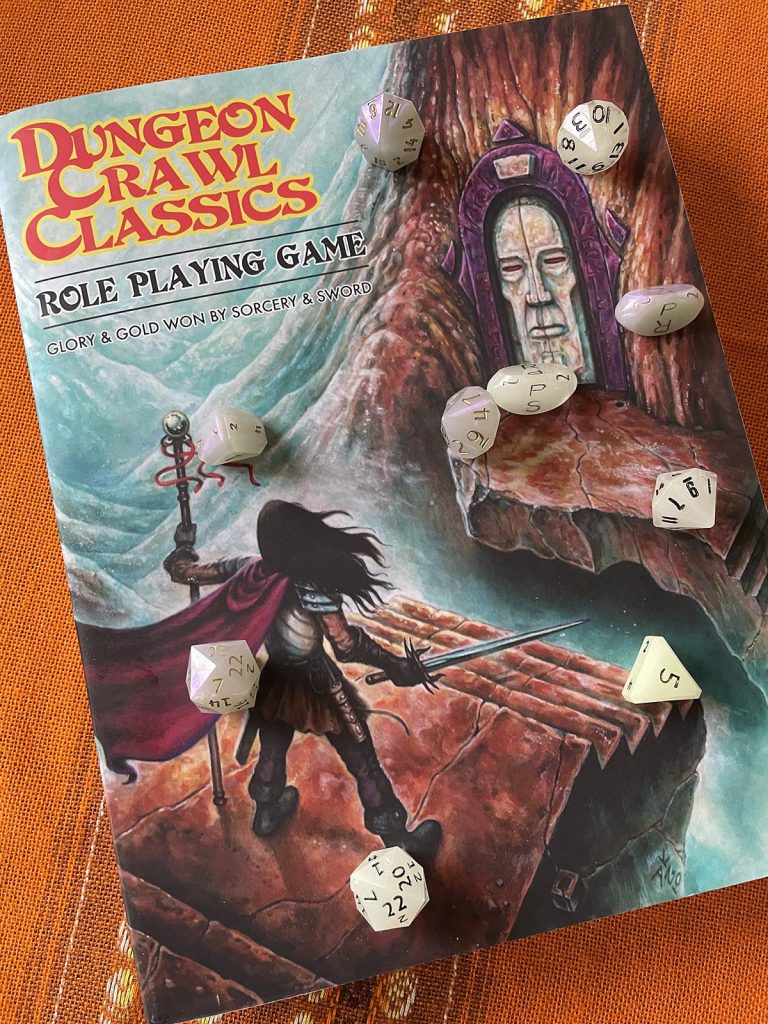

Dungeon Crawl Classics – for the D&D rebel

If OSE is loyal to the roots of D&D, Dungeon Crawl Classics (DCC) by Goodman Games is quite the opposite. While the core of DCC is certainly and unmistakingly Dungeons & Dragons (in my opinion somewhat close to third edition), this game is full of wild and imaginative innovation. Everything from character creation to spells to the imagery is tweaked, remade and re-imagined. DCC is D&D’s feral cousin. It’s a thick book, but don’t let that scare you – the rules really aren’t complex.

A myriad of great adventures have been published for Dungeon Crawl Classics, so even if you don’t choose this specific game you should keep an eye out for their supplements (remember when I said these games are usually compatible?).

Oh, it uses really wonky dice as well, which is fun.

Wrapping up

Anyway as you can see there are many ways to play Dungeons & Dragons without using books that says Dungeons & Dragons. For whatever reason you migh have to step away from Wizards of the Coast there are plenty of good (better?) options to chose from.

While a big company might own the commercial rights to the trademark, they do not own the hobby. We do.

DISCLAIMER: I am not in any way sponsored by the brands mentioned in this article. I've bought the products myself and have not been sent review copies or anything like that.

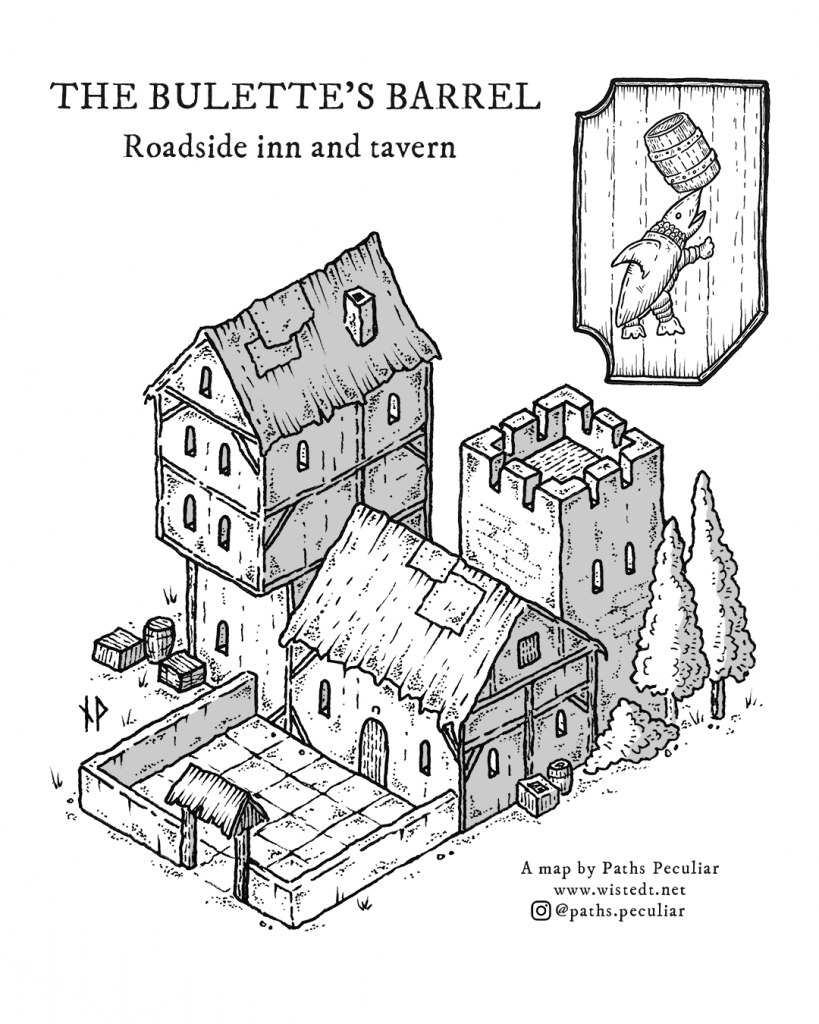

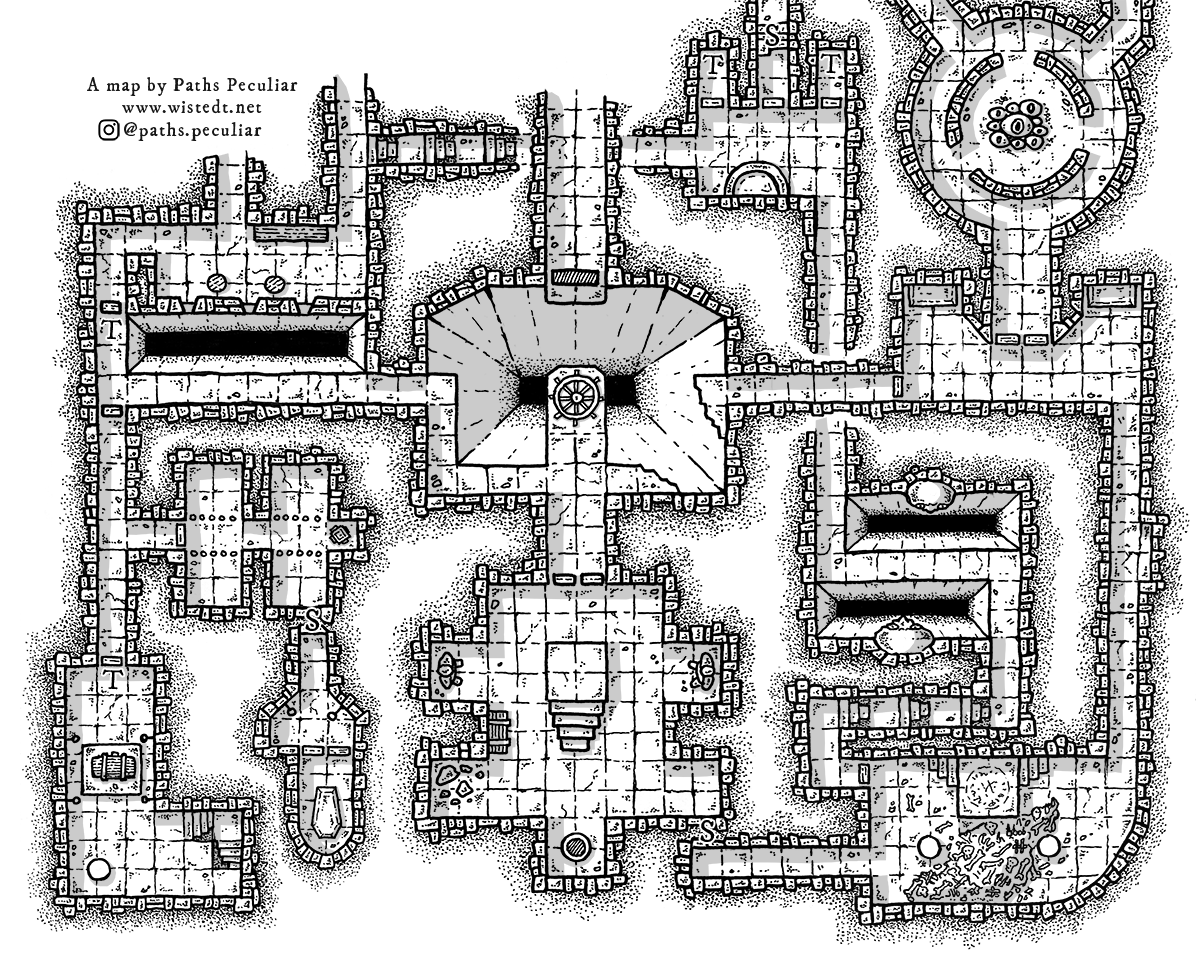

Stay awhile, and browse

I hope you liked this article. I’m not a great writer, but I’m pretty good at drawing so if you’d like to stick around for a while and check out my D&D maps, please feel free to do so! Here are some recent posts to get you started: